Numéros en texte

intégral

Numéro 16

Préface

Richard KLEIN

Introduction

Amina HARZALLAH et Imen REGAYA

Vers une réhabilitation énergétique de l’architecture moderne: Immeubles d’habitation du quartier de St Exupéry à Tunis.

Rania FARAH JAAFAR, Amina HARZALLAH et Leïla AMMAR

El Menzah I : habiter une modernité située.

Narjes BEN ABDELGHANI, Ghada JALLALI et Alia BEN AYED

16 | 2023

El Menzah I : Habiter une modernité située

Narjes BEN ABDELGHANI, Ghada JALLALI et Alia BEN AYED

Table des matieres

Introduction

1. Habiter : être dans le monde

2. El Menzah I : la porosité, un enjeu de l’habiter

3. Habiter El Menzah I

4. La performance de l’habitat

5. El Menzah I : une perspective pour repenser l’habitat

Résumé

« Qu’est-ce qu’il y a de plus réel : la maison même où l’on dort ou bien la maison où, dormant, l’on va fidèlement rêver ? » s’interrogeait Bachelard, qui précise :« je ne rêve pas à Paris, dans ce cube géométrique, dans cette alvéole de ciment, dans cette chambre aux volets de fer si hostiles à la matière nocturne » (Bachelard, 1948 ).

À la même époque, Martin Heidegger surprenait son audience constituée d’ingénieurs et d’architectes alors en charge de la reconstruction de l’Allemagne d’après-guerre, en lui annonçant que la véritable crise de l’habitation résidait dans le fait que « les mortels en sont toujours à chercher l’être de l’habitation » et venait à considérer que « l’homme habite le monde ; le monde est son espace » et que « cet entre-deux est la mesure assignée à l’habitation de l’homme» (Heidegger, 1958).

Le nouveau paradigme de « l’habiter » qu’instaure le philosophe allemand et par lequel il désigne « un rapport avec le monde » venait ébranler un autre paradigme, celui de « la machine à habiter » sur lequel se base le modèle moderniste véhiculé par les CIAM et la charte d’Athènes.

Le quartier d’El Menzah I produit à Tunis durant la reconstruction d’après-guerre avait été pensé comme la démonstration de ce modèle, offrant ainsi un cadre de vie moderne codifié pour être efficace, comme une machine, depuis l’échelle du quartier jusqu’à l’échelle de la maison. Mais la confrontation au contexte tunisien et la nécessité d’adapter le modèle moderniste aux enjeux climatiques a abouti à une production habitable au sens large, et ce à toutes les échelles depuis l’appartement, l’immeuble et jusqu’au quartier (Ben Abdelghani, 2016).

Dans cet article nous souhaitons discuter l’idée que cette production des années 40, tout en faisant référence à la machine à habiter, constitue également une alternative critique au logement minimum rationnel préconisé par le Mouvement moderne.

Le quartier se caractérise en effet par une porosité particulière qui se décline à travers la mise en œuvre de dispositions et de dispositifs permettant un filtrage ambiantal (thermo-aéraulique, lumineux, visuel, sonore, olfactif, etc.) subtilement dosé, qui s’avère favorable à l’accessibilité à l’environnement et à autrui, et par conséquent propice à l’habiter (Jallali, 2022).

En effet, le choix du site, la disposition paysagère de l’ensemble, les dispositifs de filtrage mis en œuvre à toutes les échelles de la plus urbaine à la plus architecturale, donnent lieu à une gradation du public au privé qui, en même-temps qu’elle favorise la relation intérieur/extérieur, protège le chez-soi.

Habiter, ici, prend tout son sens, au-delà de la satisfaction des exigences biologiques de confort physique : habiter c’est prendre en compte l’existant, c’est prendre soin de ce qui est là, c’est le ménager (Heidegger, 1958). Cette attention au contexte et à l’habiter, ouvrirait des pistes de réflexion pour une conception contemporaine sensible du logement social.

Mots clés

El Menzah I - quartier d’habitation à Tunis - modernité située - architecture moderne - habiter.

Abstract

El Menzah 1: Living in a situated modernity

"What is more real: the house itself where one sleeps or the house where sleeping, one goes faithfully to dream?" wondered Bachelard, "I do not dream in Paris, in this geometrical cube, in this cement alveolus, in this room with iron shutters so hostile to the nocturnal matter".

At the same time, Martin Heidegger surprised his audience constituted of engineers and architects then in charge of the reconstruction of the post-war Germany, by announcing to him that the true crisis of the dwelling resided in the fact that "the mortals are always in search of the being of the dwelling" and came to consider that "the man inhabits the world; the world is his space" and that "this in-between is the measure assigned to the dwelling of the man".

The new paradigm of "living" established by the German philosopher and by which it means "a relationship with the world" had shaken another paradigm, that of "the machine for living" on which is based the modernist model conveyed by the CIAM and the Athens Charter.

The residential district of El Menzah I produced in Tunis during the post-war reconstruction had been thought as the demonstration of this model, offering a modern living environment codified to be efficient, as a machine, from the scale of the neighborhood to the scale of the house. But the confrontation with the Tunisian context and the need to adapt the modernist model to the climatic challenges has led to a habitable production in the broadest sense, and this at all scales from the apartment, the building and up to the neighborhood.

In this paper we wish to discuss the idea that this 1940s production while referring to the machine for living, also constitutes a critical alternative to the minimum rational housing advocated by the Modern Movement.

The residential district is indeed characterized by a particular porosity which is declined through the implementation of provisions and devices allowing an ambient filtering (thermo-aerolic, luminous, visual, sound, olfactory, ....) subtly dosed, which proves to be favorable to the accessibility to the environment and to the others and consequently favorable to the inhabiting.

Indeed, the choice of site, the landscape layout of the whole, the filtering devices implemented at all scales, from the most urban to the most architectural, give rise to a gradation from public to private which, at the same time as it favors the interior/exterior relationship, protects the home.

Living, here, takes on its full meaning, beyond the satisfaction of biological requirements of physical comfort, to live is to take into account what exists, to take care of what is there. This attention to the context and to living, would open up avenues of reflection for a sensitive contemporary conception of social housing.

Keywords

El Menzah I - residential district in Tunis - situated modernity - modern architecture - living.

الملخّص

المنزه 1 : العيش في حداثة متجذرة

تساءل باشلار "أيهما أكثر واقعية: المنزل الذي ينام فيه المرء أم المنزل الذي يحلم فيه ، نائمًا ، بأمانة؟ ثم أردف قائلا "أنا لا أحلم بباريس ، في هذا المكعب الهندسي ، في هذه الخلية الأسمنتية ، في هذه الغرفة مع مصاريع حديدية معادية للمادة الليلية".

في الوقت نفسه، فاجأ مارتن هايدجر المهندسين والمهندسين المعماريين الذين كانوا مسؤولين عن إعادة إعمار ألمانيا ما بعد الحرب، بإعلامهم أن الأزمة الحقيقية للإسكان تكمن في حقيقة أن "البشر يبحثون دائمًا عن كينونة المسكن " معتبرا أن" الإنسان يسكن العالم ".

إن البراديغم الجديد "للعيش" الذي وضعه الفيلسوف الألماني والذي عين بموجبه "علاقة مع العالم" قوض براديغم "آلة للعيش فيها" الذي يرتكز عليه النموذج الحداثي و الذي تم بثه من خلال المؤتمرات الدولية للعمارة الحديثة (CIAM) وميثاق أثينا.

صمم الحي السكني "المنزه الأول" خلال فترة إعادة إعمار تونس اثر الحرب العالمية الثانية ليكون مثالا لهذا النموذج، فيوفر بيئة معيشية حديثة مقننة حتى تكون فعالة مثل آلة ،من الحي السكني الى البيت. الا ان هذا النموذج الحداثي اصطدم بالسياق التونسي والحاجة إلى تكييفه مع المناخ المحلي فأسفر ذلك عن إنتاج عمارة مواتية للعيش بالمعنى الهايدجيري ، وهذا على جميع المستويات من الشقة الى المبنى الى الحي السكني.

ويتميز حي المنزه الأول بمسامية برزت بالخصوص في التشكيلات المعمارية والوحدات البنائية التي تقوم بتكييف الحرارة ودوران الهواء والاضاءة والإبصار والصوت والشم بجرعات دقيقة، مما يثبت أنها مناسبة لتحسين الإتصال بين الداخل والخارج للمبنى والتواصل والتفاعل مع الآخر وبالتالي تساعد على العيش فيها.

ان اختيار موقع الحي وتهيئة مناظره الطبيعية وتصميم التشكيلات المسامية ان كانت معمارية أو عمرانية، أدت إلى ظهور تدرج من العام إلى الخاص وهو ما يعزز في نفس الوقت العلاقة بين الداخل و الخارج ويحمي المسكن.

تأخذ الحياة هنا معناها الكامل والشامل، بما يتجاوز تلبية المتطلبات البيولوجية للراحة الجسدية، فالعيش يعني مراعاة ما هو موجود، والاهتمام بما هو موجود، والتكيف معه . ومن شأن هذا الاهتمام بالسياق والسكن أن يفتح آفاقًا للتفكير بمفهوم معاصر للسكن.

الكلمات المفاتيح

المنزه الأول - الحي السكني بتونس - حداثة متجذرة - العمارة الحديثة - العيش.

Pour citer cet article

BEN ABDELGHANI Narjes, JALLALI Ghada et BEN AYED Alia, « El Menzah I : Habiter une modernité située », Al-Sabîl : Revue d’Histoire, d’Archéologie et d’Architecture Maghrébines [En ligne], n°16, Année 2023.

URL : https://al-sabil.tn/?p=3315

Texte integral

L’idée de cet article part du constat que le quartier d’El Menzah I est agréable à vivre tant du point de vue de ses habitants que de celui de ses visiteurs occasionnels. Nous posons l’hypothèse que les architectes à l’origine de sa conception ont accordé la primauté à l’habiter. Nous considérons que cet ensemble est non seulement une référence patrimoniale moderniste à sauvegarder, mais que, de plus, il pourrait constituer une source d’inspiration pour de futurs projets où « habiter » prend sens.

La question de l’habiter est au centre des préoccupations des penseurs contemporains : qu’ils soient philosophes, anthropologues ou encore professionnels de la ville, tous s’interrogent sur les possibilités de co-habiter entre humains, mais aussi avec les autres formes de vie (animales, végétales, etc.)

Militant pour une écologie politique, le philosophe Fédéric Neyrat1 s’interroge : « Où sommes-nous ? Ce qui veut dire : où habitons-nous ? Comment, et dans quelles conditions ? Selon quels rapports avec les autres ? Avec les non-humains, avec les autres formes de vie ? » Il considère que « si ces questions se posent avec autant d’acuité, c’est que la possibilité même de l’habitation est aujourd’hui mise en cause ».

Cette mise en cause est soulignée également par l’anthropologue Bruno Latour qui dénonce le projet de globalisation des Modernes et leur déni des limites de la planète. Portés par l’impératif d’une croissance mondialisée, nous découvrons qu’elle n’est pas soutenable. S’extériorisant de la « nature », les humains ont jusque-là agi en tant que dominants sans considérer les autres vivants « comme autant d’agents participant pleinement aux processus de genèse des conditions chimiques et même, en partie, géologiques de la planète »2. Adoptant le point de vue surplombant des sciences de la nature, ils ont exploité les ressources de la planète sans en prendre soin. Le résultat est que nous nous retrouvons tous actuellement « devant un manque universel d’espace à partager et de terre habitable ». Le Globe n’est plus assez grand pour y loger les humains et leur projet de modernité universelle.

De son côté, dans sa théorie atmosphérique, le philosophe Peter Sloterdijk soutient comme préalable que l’homme est toujours plongé dans un climat englobant, pour autant il est en mesure, techniquement, de le modifier pour l’adapter à sa convenance, selon différents ordres de priorité. Cette reconfiguration climatique, conditionnant la vie, produirait des sphères atmosphériques de cohabitation hybrides, combinant des facteurs hérités biophysiques (rayonnement solaire, couvert végétal, vents dominants) et une volonté de changement, fruit de certaines représentations de la qualité de l’habiter qui dépasse le clivage réducteur de nature et culture. Dans ce sens « "climat" désigne […] d’abord une dimension communautaire et seulement après, un état de fait météorologique »3. La « sphéro-immunologie » permet de penser les conditions de possibilités sans lesquelles aucune vie humaine ne pourrait se développer. Il ne s’agit donc pas de constituer des espaces coupés de tout extérieur, mais de ménager des filtres plus ou moins intenses pour construire des sphères d’intimité, mais toujours en coprésence avec les autres habitants qu’ils soient humains ou non humains. Cette coprésence est donc associée à un sentiment commun d’un même souffle de vie, qui impose des logiques d’attention aux autres.

C’est de cette coprésence dont il est question à El Menzah I. Arpentant ce quartier à l’occasion de nos recherches communes, nous la ressentons intimement. Nous envisageons dans cet article de tenter d’en expliciter l’origine.

Au lendemain de la guerre, la reconstruction de la Tunisie a représenté un moment singulier de son histoire, imprégné par une volonté réformiste de la part de l’administration coloniale. La relève des ruines devient ainsi l’occasion de repartir sur de « nouvelles bases » pour mieux aménager l’ensemble du territoire.

Aussi, très vite, la question du simple recasement des sinistrés se transforme en une politique de logement pour laquelle l’équipe des reconstructeurs met en place une doctrine générale qu’ils essayeront d’appliquer en créant de nouveaux lieux de séjour dans les villes et dans les campagnes tunisiennes4.

A la veille de l’indépendance, El Menzah I est un quartier d’habitation en ville qui témoigne du passage des idées formulées au niveau de cette doctrine vers leur transcription matérielle dans l’espace.

Réalisé entre 1945 et 1953 à Tunis, le quartier est publié à plusieurs reprises - dans la revue Architecture d’Aujourd’hui (n° 20 en 1948 et n°60 en 1955) ainsi que dans plusieurs publications tunisiennes- et présenté par ses concepteurs comme un premier " maillon de la chaine des zones résidentielles de demain5, un « lotissement-pilote6 » et dans le discours de l’administration de la reconstruction comme une « synthèse », une « démonstration » et un « modèle » à suivre7.

La forme du quartier a été évolutive au gré des équipes8 qui se succèdent pour le penser, si bien que la forme finale qu’il prend manifeste la synthèse d’un ensemble de modèles et d’expériences qui coexistaient à l’époque de son édification : entre le modèle urbain issu de la doctrine de la régularisation de l’école française d’urbanisme qui battait en brèche, celui envahissant des « progressistes 9» des CIAM et leur charte d’Athènes qui avait le vent en poupe, l’expérience des nouvelles villes du « Grand Londres » se voulant plus humaines et celle de Radburn aux Etats Unis, première cité jardin ayant été pensée pour être adaptée à l’intrusion de l’automobile.

Au confluent de ces influences qui se conjuguent à la topographie et au climat tunisien et au-delà des divergences des concepteurs, le quartier se cristallise comme un lieu pensé pour qu’on aime y habiter.

Mais avant d’avancer plus loin dans notre propos, il convient de préciser la notion même d’habiter.

1. Habiter : être dans le monde

Dès les années d’après-guerre, Martin Heidegger soutenait, face à une audience constituée d’ingénieurs et d’architectes alors en charge de la reconstruction de l’Allemagne, que la véritable crise de l’habitation résidait dans le fait que « les mortels en sont toujours à chercher l’être de l’habitation »10. Habitation qu’il étend au-delà du logement. Convoquant les mots et leur étymologie, il s’attache à questionner l’être de l’habitation. Le vieux mot bauen, se rattache à bin (suis), et dans ce sens, « ich bin, du bist, (je suis, tu es), veulent dire : j’habite, tu habites. La façon dont tu es et dont je suis, la manière dont nous sommes sur terre est le buan, l’habitation. Être homme veut dire être sur terre comme mortel, c’est-à dire habiter ». Poursuivant son cheminement lexicographique, Heidegger souligne que bauen signifie aussi enclore, soigner, cultiver (notamment un champ), ménager et il en vient à l’idée que « le trait fondamental de l’habitation est ce ménagement ». Ce ménagement ou cette attention à la terre, il l’étend au ciel, aux divins et aux mortels dont il fait un tout qu’il nomme le quadriparti. De nos jours, dans la sphère architecturale, nous parlerions d’attention portée au site, au climat, à l’esprit des lieux, au genius loci.

Le nouveau paradigme de « l’habiter » instauré par Heidegger et par lequel il désigne « un rapport au monde », prend le contre-pied d’un autre paradigme, celui de « la machine à habiter » sur lequel se base le modèle moderniste véhiculé par les CIAM et la charte d’Athènes.

En plus d’une normalisation de l’habitation conçue pour un homme universel, sans prise en compte des situations climatiques différenciées, la « machine à habiter » préconise soit l’effacement des limites entre intérieur et extérieur (avec le culte de la transparence), soit au contraire, une séparation à outrance de la sphère privée et de la sphère publique conduisant à un urbanisme de zoning distinguant des activités de travail et d’habitat, la mobilité automobile et piétonne, etc.

Or, il s’avère que la production moderniste d’El Menzah I, quoique se revendiquant de ces principes, les transgresse quelque peu puisqu’elle se caractérise par une porosité graduelle dont on fait l’hypothèse qu’elle est à l’origine de son habitabilité. Habitabilité dont témoignent ses habitants.

2. El Menzah I : la porosité, un enjeu de l’habiter

Nous nous proposons dans cet article de décrire la porosité en question et d’évaluer sa pertinence du point de vue de l’habiter. Tant à l’échelle du quartier, qu’à celle de l’immeuble, voire de l’appartement, El Menzah I apparaît comme une composition graduelle poreuse comportant de nombreux dispositifs de filtrage visuel, sonore et thermo-aéraulique qui se conjuguent pour dessiner des variations affectives qui viennent rythmer le vécu des utilisateurs.

Issue du monde de la physique la notion de porosité se consacre moins à la structure des milieux poreux qu’aux phénomènes très variés dont ils peuvent être la scène, en cas d’état de non équilibre (mécanique, thermodynamique, thermique, chimique, électrique…)11. Transposée en architecture, cette démarche modale qui met l’accent sur les interactions en jeu permet de mettre au jour la dynamique qui préside à l’expérience vécue. En effet, dépassant les limites des paradigmes objectivistes fixistes, la porosité ouvre la perspective sur la dynamique des échanges atmosphériques. Envisager El Menzah I, non plus comme un ensemble d’objets bâtis, mais comme une atmosphère, un ensemble de « bulles atmosphériques » (Sloterdijk, 2013) plus ou moins connectées les unes aux autres, autorisant une circulation savamment dosée de l’air, de la lumière, du son, etc. mais également des échanges intersubjectifs, nous permet d’expliciter en quoi la configuration de ces atmosphères est propice à l’habiter.

La configuration poreuse d’El Menzah I s’avère non seulement confortable, mais elle est au fondement même de l’habiter. Accordant à la modalité visuelle sa juste valeur et favorisant la circulation des flux et des fluides invisibles qui lient les humains entre eux, et avec les non humains, la porosité en question permet donc de construire les sphères d’intimité, en coprésence avec les autres formes de vie qu’évoquait Sloterdijk. Associée au souffle de vie communément partagé, cette coprésence, rappelons-le, appelle une attention au site, aux autres. Subsumant le registre du sensible, elle engage une ouverture vers le suprasensible (voire le divin)12, conditionnant ainsi l’habiter au sens où Heidegger l’entendait.

3. Habiter El Menzah I

3.1. Le lieu de séjour de l’habitant

Un passage qui figure dans les rapports rédigés dans les premières années de la reconstruction sous le titre "Doctrine" (et qui est repris par Bernard Zehrfuss dans un article publié en 1945 dans la revue l’Architecture d’Aujourd’hui13) permet de saisir l’importance de la question de l’habitat vue comme cruciale pour réussir la relève économique de la Tunisie après la guerre :

"Ici, le problème social est intimement lié aux problèmes économiques et techniques, car, on ne peut demander à quiconque un effort sérieux et régulier si on ne lui assure, en compensation, un logement et des établissements d'alimentation, d'assistance et de santé, de culture, et des équipements sociaux et sportifs lui offrant des commodités et un agrément d'existence suffisante pour développer sa santé, son énergie, sa capacité et sa continuité d'efforts. Aussi, le Service de l’Urbanisme du Secrétariat général du gouvernement s’attache-t-il surtout et en première urgence à contribuer à améliorer les conditions de travail, de vie et d’habitat de la partie de la population susceptible d’aider au maximum le relèvement économique du pays"14.

La qualité du lieu de séjour qui occupe le centre de cette équation tient ainsi à sa capacité à assurer « un agrément d’existence » pour ses occupants.

Mais pour esquisser la maison du travailleur épanoui, les architectes de la reconstruction regardent bien au-delà du solide englobant sa sphère domestique privée et s’engagent à façonner le cadre général d’une quotidienneté qui s’établit depuis et vers la maison.

En disant : « Nous nous sommes surtout appliqués, dans nos études et nos réalisations en matière d’urbanisme, à mettre en avant la cause de l’habitat »15, Bernard Zehrfuss ne fait que souligner cette orientation.

Singularité de l’histoire, le moment de la reconstruction permettait à ces architectes d’appliquer les postulats athéniens qui lient architecture et urbanisme. Ils prendront ainsi en charge les différentes échelles en concevant la maison dans l’immeuble, dans le quartier, dans la ville de Tunis.

Cette « vue d’ensemble » défendue par Bernard Zehrfuss conduit à façonner le réceptacle de la quotidienneté du travailleur depuis le siège qu’il occupe confortablement dans un tramway pour rejoindre son travail, jusqu’au fauteuil où il s’installe face à une fenêtre de son séjour, lui permettant de voir au dehors.

Autant dire que pour le bien-être de l’habitant et de la famille, ce sont d’abord des scénarios de vie qui sont envisagés par les architectes et qui prennent par la suite corps dans des dispositifs spatiaux qu’ils façonnent, depuis la ville jusqu’à la maison.

Scénarios de vie prototypiques que la Charte avait bien ancrés dans leur esprit, que le Musée social partage dans les grandes lignes, et que les expériences les plus contemporaines à leur époque confortent.

Que promettent les architectes dans ce cadre de vie global se voulant épanouissant ?

Des habitants en bonne santé car installés dans des lieux ensoleillés et aérés, éloignés de la pollution et du bruit de la ville ; profitant de la proximité des « conditions de la nature » que sont air, soleil et verdure et qui leur procurent bien-être et évasion tous les jours ; rejoignant leur lieu de travail sans souffrir des longues distances et des embouteillages ; marchant dans les rues en toute sécurité ; trouvant aux pieds de leurs maisons les "commodités de la vie courante" pour « économiser au maximum leur énergie »16 et pour « réduire leurs gaspillages de temps et d'argent »17.

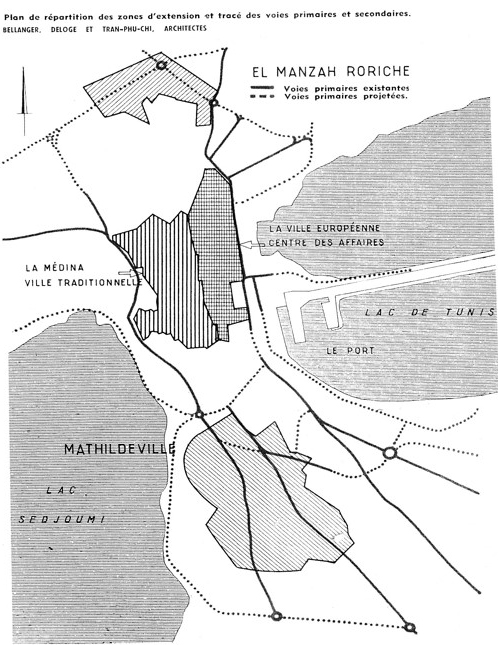

Source : AA n°60, 1955

Pour donner corps à ces conditions de séjour, les concepteurs d’El Menzah I ont défini sa situation dans la ville, sa relation au réseau viaire et ce n’est qu’ensuite qu’ils se sont consacrés à sa configuration.

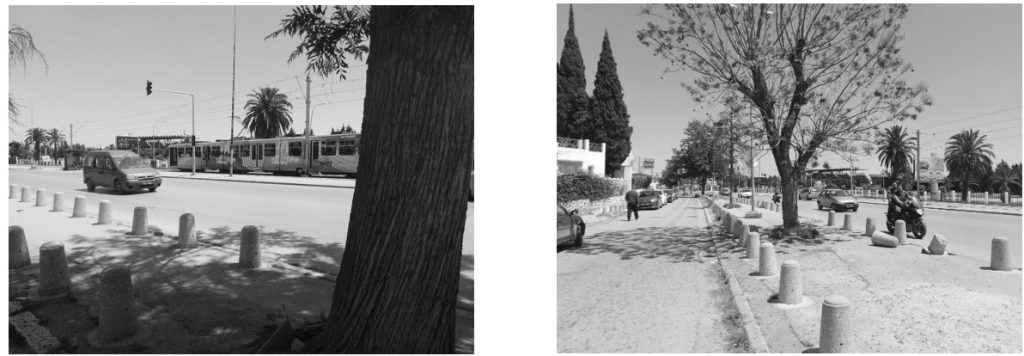

Le quartier se présente ainsi et en premier lieu comme un pied à terre savamment situé dans la ville de Tunis, accroché à l’un des flancs les mieux orientés et aérés de ses coteaux sud-est et raccordé aux lieux de travail par « des communications commodes » dont la durée « n’excède pas15 min à la vitesse moyenne de 60Km/h » ou une « demi-heure de marche à pied ».

Les paroles des architectes de la reconstruction et le dispositif spatial qu’ils mettent en place à l’échelle urbaine dévoilent ici leur adhésion aux prescriptions de la Charte d’Athènes. Ils ont eu recours à la mesure « distance-temps » qui y est prescrite pour planifier des parcours journaliers rapides et ont connecté le quartier d’habitation à un réseau viaire périphérique constitué par une large voie à grand trafic et une ligne de tramway.

3.2. Le quartier : Habiter avec les éléments

Ce n’est pas par hasard qu’en ceinturant le quartier sans l’approcher, la voie à grand trafic le raccorde à tout point de la ville et le détache au même moment de l’environnement d’insécurité, de nuisances sonores et sanitaires qu’elle génère.

Il s’agit d’une mise en forme du schéma spatial décrit dans la Charte d’Athènes qui est ici agrémenté par l’installation d’une deuxième voie plantée d’arbres qui prolonge la circulation interne du quartier parallèlement à la grande voie.

Derrière, apparait, en profondeur, un milieu de vie que cette épaisseur urbaine (la voie et les arbres) enveloppe, le retranchant du vacarme et des pollutions.

Ce paysage se manifeste depuis la ligne du métro. Prudemment, la rue à grand trafic où circulent des voitures dans les deux sens peut être traversée.

A partir de cette voie latérale, et à mesure que l’on avance dans le quartier, les bruits du métro, des voitures, les fumées qui s’en dégagent, s’amenuisent et sont supplantées progressivement par les gazouillis des oiseaux qui occupent le feuillage luxuriant des jacarandas, traversé par des faisceaux lumineux qui se projettent au sol.

Le milieu qui s’affirmait de loin visuellement, accuse maintenant une présence imprégnée de pénombre et de nouvelles sonorités.

Les arbres peuplés d’oiseaux ne sont pas étrangers à l’affirmation de ce dedans. Leur présence répond à un art de la composition urbaine où l’alignement des arbres est de mise, pour accompagner le piéton-promeneur, pour souligner les perspectives, pour lui procurer de l’ombre et de la fraicheur. Conformément au modèle de la cité jardin, les concepteurs en usent autant que de morceaux de verdures plus épais découpés dans le tracé des rues, des jardins de tailles différentes ponctuant différents sous-espaces du quartier.

L’espace vert de la Charte d’Athènes envisagé comme « prolongement du logis », « procurateur d’oxygène » et « propice aux ébats des enfants »18 prend ici place en revêtant la forme que lui attribue le modèle rival de la cité jardin. À plusieurs endroits, des maisons se regroupent autour de la pénombre, de la fraicheur et du silence19.

En réalité, les voitures n’ont pas déserté le quartier, mais elles circulent moins vite. Les reconstructeurs l’avaient prémédité.

La voie qu’ils ont rejetée à la périphérie du quartier pour assurer une liaison facile avec le lieu de travail sans exposer les habitants au danger de la circulation à grande vitesse fait partie d’un réseau viaire hiérarchisé qui se base sur la séparation emblématique moderne entre la rue piétonne et la rue véhiculaire.

Dans ce système hiérarchisé, codifié dans la Charte, sont préconisées des « voies primaires » à grande vitesse à écarter absolument du quartier d’habitation, des « voies secondaires » à vitesse modérée dont la présence est tolérée à l’intérieur du quartier à côté de « voies tertiaires » réservées exclusivement au piéton.

Les ronds-points, les voies à sens unique, le dispositif en cul de sac que les architectes retiennent de l’expérience de la cité de Radburn aux Etats-Unis leur permettent d’assurer la fluidité d’une circulation automobile à vitesse modérée à l’intérieur du quartier alors qu’un système complet de trottoirs est parallèlement mis en place pour la sécurité du piéton.

Le système de trottoirs qui se superpose au tracé des rues favorise une promenade guidée par les alignements d’arbres, ponctuée par des mises en perspectives et par la variation des volumes des immeubles et des maisons individuelles.

Lorsqu’on marche dans le quartier, on ne peut perdre de vue les différentes porosités ménagées à cette échelle car les limites instaurées par les architectes s’ouvrent et se ferment selon des gradations multiples, en fonction de leur matière, et de l’environnement avec lequel elles dialoguent.

A un moment de cette expérience spatiale quotidienne, se profile devant l’habitant un porche urbain - installé au centre du plus grand immeuble du quartier « Balkis » et dans l’axe de sa plus grande rue par souci de composition urbaine. Le dispositif invite à découvrir progressivement les deux rives qu’il génère par sa présence. Le derrière et le devant sont ici définis et éloignent d’un paysage urbain qui aurait pu être atomisé par la répétition systématique des barres d’immeubles.

De par sa porosité visuelle, le porche entretient un lien particulier avec l’espace vert qui marque le centre du quartier et invite à une marche depuis et vers cette verdure qui peut être traversée et où on pourrait séjourner.

Mais ce fragment de nature prolonge aussi les logis depuis les fenêtres et les loggias qui le prennent pour repère.

L’enfilade des alvéoles placées au front sud-est des appartements constituent des limites épaisses qui créent un entre-deux, entre l’univers intime de la maison et le dehors au contact de cette nature. Largement poreuses, elles permettent d’ouvrir et de fermer à la fois pour composer avec le climat tunisien.

Pour y accéder et saisir leur capacité à installer l’habitant à l’extérieur, à proximité de l’air, de la verdure, du soleil et des vues agréables, tout en protégeant l’intérieur de sa maison des regards indiscrets et de l’hostilité des éléments, il faudrait les rejoindre directement par les escaliers dans les 2 premiers immeubles du quartier, « Le Zodiaque » et « Virgile ».

Dans ces deux immeubles en particulier, la promenade quotidienne de l’habitant (qui retrouve sa maison après une journée de labeur, d’activités ou d’études selon les profils) se poursuit depuis le trottoir ombragé, ponctué par des alignements d’arbres, jusqu’à la cage d’escalier ouverte qu’il arpentera en côtoyant les éléments pour accéder à sa loggia privée.

Si la cage d’escalier est ouverte, c’est pour une raison principale, celle de favoriser la circulation des flux d’air dans un pays chaud comme la Tunisie, mais la conséquence spatiale est d’envergure.

Chaque jour, les habitants des niveaux hauts de ces immeubles sont engagés dans un parcours qui leur offre une expérience de leur lieu de vie rythmée par une alternance entre intérieur et extérieur, entre lumière et pénombre ; vécue au quotidien et en fonction des saisons.

Source : N. Ben Abdelghani 2022.

3.3. Le quartier : habiter avec les autres

Habiter sa maison, c’est aussi habiter avec ses voisins les plus proches et ceux que l’on rencontre dans des lieux partagés.

On avait reproché au modèle moderne représenté par la Charte sous forme de multiples barres lamelliformes perdues dans un océan de verdure, l’atomisation de l’espace du quartier d’habitation et son incapacité à supporter et à catalyser les liens sociaux.

Avant même que ces critiques ne deviennent persistantes, les concepteurs d’El Menzah I portent une attention particulière à la question du vivre ensemble.

La géométrie empruntée au modèle de la cité jardin leur a permis de configurer à travers les ilots urbains, des « lieux situés » plutôt qu’un "espace, « cartésien » et « atopique »20 généré par la répétition systématique des barres d’immeubles.

Les micro-lieux différenciés et hiérarchisés qui en résultent, peuvent être observés comme constituant autant d’occasions spatiales pour rencontrer les autres et éventuellement développer des sentiments d’appartenance aux espaces partagés.

Mais s’ils réussissent le pari de configurer un lieu de vie pour des groupes humains et non pour une masse anonyme considérée du seul point de vue numérique, c’est parce qu’au-delà de la géométrie, ils accordent une grande attention à la question du nombre.

Pour eux, El Menzah I est un « un groupe d’habitation » autonome par ses propres organes collectifs, destiné à 2500 habitants avec une densité moyenne de 250h/H.

Il représente ainsi la plus petite unité de voisinage d’un ensemble prénommé d’abord « Cité de Crémieuxville » et par la suite « Menzah Roriche » et qui consiste en une fédération de collectivités élémentaires de 30.000 à 50.000 personnes, chacune d’elle ayant ses équipements et un système économique propre et est subdivisée à son tour en quartiers (5.000 à 10.000 habitants) et groupes d’habitations (1.000 à 2.500 habitants) équipés en organes collectifs21.

L’organisation des nouvelles cités résidentielles projetées à Tunis selon ce système de cellules hiérarchiques et autonomes22 est un choix23 qui avait été fait dès le départ par les architectes de la reconstruction en se référant au « principe des unités résidentielles du grand Londres »24.

Pour S. Giedion, l’expérience de ces "new towns"25 londoniennes représente une tentative « pour rendre les rapports humains plus intimes en fragmentant la ville en « unités de voisinage »26.

Les concepteurs du quartier d’El Menzah I en sont conscients, comme le laisse entendre l’argumentaire de Michel Deloge qui voit dans ce système hiérarchique le moyen de « favoriser entre les habitants vivant à l’intérieur d’une collectivité élémentaire ainsi réorganisée les contacts qui favorisent la sociabilité afin de supprimer ce que l’on a pu appeler « ce monstre social » que constituait le citadin anonyme isolé au milieu de ses semblables »27.

La question du nombre apparait ici déterminante et elle réapparait à l’échelle architecturale à travers d’autres attributs empruntés à la cité jardin londonienne que sont l’alternance entre l’habitat collectif et l’habitat pavillonnaire ainsi qu’une verticalité modérée des immeubles permettant ainsi d’éviter l’effet d’entassement des habitants.

La configuration du « Zodiaque » et de « Virgile » montre qu’à l’échelle de l’immeuble également, l’effet d’entassement est évité.

L’aboutement horizontal de quatre immeubles doubles pour générer les barres d’habitation de manière évolutive, conduit à une réduction du nombre de voisins : 32 voisins partagent une même barre, 8 partagent chaque immeuble double et sa cage d’escalier ; 2 voisins partagent chaque palier.

La fragmentation successive des lieux de vie aboutit ici à un système hiérarchisé d’unités de voisinages qui s’emboitent depuis les 40 000 habitants qui partagent une même « collectivité » jusqu’au voisin qui partage le palier, permettant sans doute d’affirmer des appartenances, des appropriations et de catalyser les liens sociaux.

3.4. La liberté d’habiter sa maison

La dérive du modèle progressiste pris en charge par des administrations pressées de loger le grand nombre consiste à caser une masse sans aucune considération de la dimension sociétale. À l’échelle de l’appartement aussi, lorsque la question quantitative supplante les promesses humanistes de la maison moderne minimale, celle-ci se transforme en un agrégat de pièces monofonctionnelles encapsulant à son tour le scénario domestique dans un organigramme fonctionnel.

Parmi les réflexions contemporaines qui cherchent toujours à dépasser cette réduction fatale et à donner place à la question de l’habiter, celle que mène l’architecte Sophie Delhaye part d’une conscience de la complexité de la vie domestique et de la nécessité de mettre en forme une architecture qui est en mesure de l’accueillir et de lui permettre d’évoluer.

Par exemple, dans son projet de 55 logements à Nantes, le concept de « la pièce plus » faisant partie d’une collection de pièces organisées autour d’un patio et singulière de par sa position dans la maison permet de répondre à cette complexité, car c’est l’habitant qui l’investit en fonction de son propre scénario de vie et de l’évolutivité de ce scénario dans le temps.

À la fin des années quarante, les immeubles Le Zodiaque et Virgile offraient par leur configuration inédite ces mêmes libertés à leurs habitants.

La mise en forme d’une loggia qui longe les pièces de l’appartement et qui les relie directement à l’entrée, multiplie les possibilités d’utilisation de l’une des deux pièces du fond pouvant devenir chambre de l’adolescent qui bénéficie ainsi d’une marge d’indépendance tout en vivant avec sa famille, la chambre de la grand-mère, un bureau qui reçoit des étrangers à la maison, etc.

La loggia joue ici pleinement le rôle du patio qui structure l’ensemble, qui définit sa relation avec l’extérieur et qui hiérarchise les parcours28 et les rapports entre les différents usagers de la maison.

Les investigations conduites sur l’immeuble le Virgile29 pour en évaluer le régime thermique, viennent conforter cette hypothèse. Autant la mesure technique que la parole habitante recueillie sur site confirment l’existence de cette gradation poreuse si propice à l’habiter.

Source : N. Ben Abdelghani, 2016

4. La performance de l’habitat

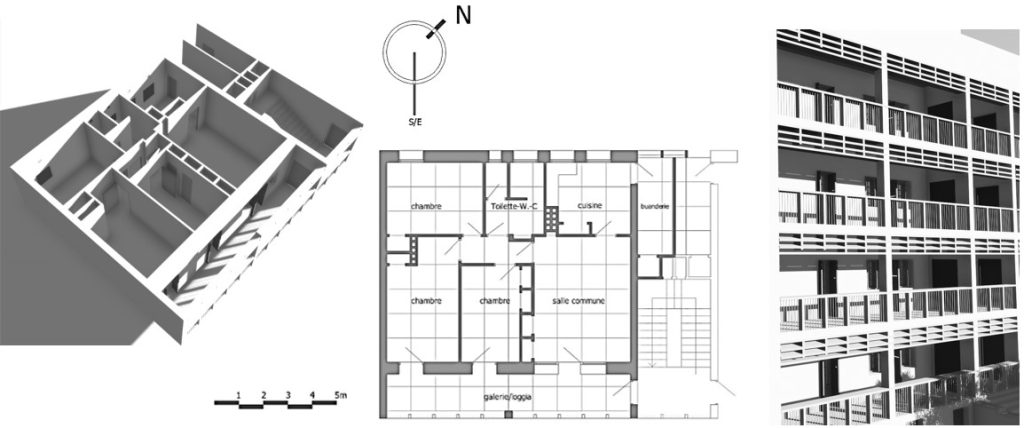

L’immeuble Virgile30 fait partie de la première tranche du quartier qui est constituée de 9 immeubles en barre. L’analyse détaillée du dispositif d’entrée met en exergue une gradation du public au privé tant au niveau de l’urbain qu’au niveau de l’immeuble. Cette gradation se matérialise par différents filtres qui ponctuent le parcours depuis l’espace public de la rue à l’espace semi-public – constitué du retrait de l’immeuble, et de l’espace vert qui le précède ainsi que des cages d’escalier – jusqu’à l’espace semi-privé – matérialisé par les loggias faisant office de dispositif d’entrée des appartements – pour enfin atteindre l’espace le plus privé et intime du logement (voir figure 1). On ne peut s’empêcher de se rappeler la gradation dans la maison traditionnelle avec la ruelle, l’impasse, la driba et la skifa.

Cette gradation du public au privé obtenue grâce à une série de dispositifs filtrant, permet de protéger l’habitant des regards indiscrets, tout en ménageant une relation privilégiée avec l’environnement. Ainsi, l’habitant se sent-il libre d’établir éventuellement une relation avec l’autre. L’ambiance change en passant d’un niveau d’intimité à un autre. Dans l’espace public, l’habitant profite de l’ombre des arbres, du calme de l’impasse au fond de laquelle l’immeuble prend place, bien en retrait des rues bruyantes avoisinantes. Dans l’espace semi-public, il peut apprécier les chants des oiseaux, le rire des enfants jouant dans le jardin. Dans l’espace semi-privé, il pourra savourer l’ouverture vers l’extérieur, l’ensoleillement dans les mois froids de l’année, les odeurs de la cuisine. Dans l’espace privé, il jouit de sa liberté, de son intimité et de son confort. Cette relation entre l’habitant et le lieu de sa résidence passe ainsi par des interactions dynamiques entre soi et son environnement physique et social. En effet, si on en croit Yvonne Bernard31 : « le sentiment d’être chez soi est d’abord vécu dans l’espace du logement mais il peut être également ressenti, dans un espace public, dans un quartier, dans une ville ». Ainsi, grâce à cette gradation d’intimité, les habitants du Virgile sont capables de s’approprier le lieu en exploitant son potentiel sensoriel, spatial et social afin de trouver leur confort.

La loggia orientée sud-est doublant la façade dotée d’orifices d’aération configure une façade épaisse particulièrement poreuse à des effets sensibles qui affectent le vécu des habitants. Les principes de conception de ce dispositif reposent essentiellement sur la gradation et le filtrage. Ces effets de filtrage prennent forme à travers « l’orientation générale sud-est face au lac. L’accès de chaque appartement par une loggia de 1m50 de largeur qui s’étend à chaque étage sur toute la longueur de la façade. Cette disposition souvent adoptée dans les pays chauds évite l’entrée directe des appartements sur la cage d’escalier et permet la parfaite ventilation de celle-ci. »32. Cette gradation rythmant la transition du public au privé est caractéristique d’El Menzah I. En effet, un lieu n’est-il pas « souvent caractérisé par la transition qui nous y amène 33» ? La façade épaisse devient alors un espace qui invite au partage et à la quête de la fraîcheur, à la quête du souffle et à la quête de l’ombre. Cette lisière, entre l’extérieur et l’intérieur, invite quotidiennement à se poser et à partager des moments agréables.

« l’été, je préfère m’installer sur le balcon pour prendre mon café… généralement à partir de 18h c’est agréable… en plus le quartier est calme surtout que l’immeuble se trouve dans une impasse… donc je profite pour regarder la rue et le paysage…) » Aida (habitante du Virgile 3ème étage).

Pour accéder à l’appartement, l’habitant traverse une cage d’escalier couverte ouverte (Figure 2) exposée à la circulation de l’air et à l’ensoleillement. La ventilation de cet espace refroidit les parois des appartements, contribuant au rafraichissement de l’espace intérieur. Cette conception efficace pendant la période chaude de l’année présente, toutefois, des inconvénients pendant l’hiver. La porte d’entrée de chaque appartement sépare la cage d’escalier de la loggia du logement. Le palier devient ainsi un espace de transition à l’extérieur de l’appartement et la loggia un espace semi-ouvert à l’intérieur de l’habitation (Figure 3).

La loggia, quant à elle, constitue une extension de la circulation verticale. Elle devient ainsi un dispositif d’entrée et de transition entre l’entrée et la salle commune. C’est un espace tampon entre l’extérieur et l’intérieur qui permet aux habitants d’être en contact direct avec l’espace public et la nature tout en préservant leur intimité. Ne pouvant être associée exclusivement ni à l’intérieur, ni à l’extérieur, cet espace de transition correspond à un entre-deux qui dessine un parcours d’entrée. En plus de son rôle de modérateur thermique et solaire, la loggia est utilisée, selon les propos recueillis des habitants, pour étendre le linge ; décorée de plantes en pot et meublée de banquettes et assises, elle sert fréquemment d’espace de détente. Elle permet ainsi aux occupants d’être en relation directe avec l’extérieur tout en restant dans leur espace intime et privé. Il est à noter que cette loggia est particulière par rapport aux autres immeubles puisque le mur intérieur qui la sépare de l’appartement présente des orifices de ventilations augmentant ainsi son degré de porosité.

« On n’a pas de vis-à-vis, juste devant il y a une banque et une fédération de football … en plus personnellement je n’en ai rien à faire... Même si quelqu’un passe devant l’immeuble je ne le regarde pas... je fais tout pour éviter les regards indiscrets en évitant de les regarder directement... je m’installe pour lire un livre, ou surfer sur le web ou boire un café ou pour profiter de la vue sur la verdure et du soleil… avant, j’étendais mon linge du coté de mon jardin mais depuis quelques temps, j’ai décidé de le faire du côté du balcon (loggia) car il y a moins de vent... Je ne sais pas si c’est à cause de l’orientation ; je n’ai aucune idée... en tout cas le vent est très agréable en été surtout qu’avant il y avait des oliviers plantés donc c’est plus frais… » Houda

« Tu sais, je me sens tellement bien dans cet appartement… il est aéré, lumineux, agréable…il te permet de mener une vie paisible… » Houda

Source : G. Jallali, 2022.

La simulation numérique34 montre que le dispositif de la façade épaisse génère de l'ombre sur toute la façade de l'appartement et contribue au confort thermique. Les ouvertures des chambres et de la salle commune ne sont pas exposées directement au soleil d’été, les chambres ne sont donc ensoleillées que pendant une courte période de la journée. Tandis qu’en hiver le soleil étant bas, la loggia ne présente plus d’obstacle pour les rayons solaires. Ces derniers atteignent les espaces intérieurs et réchauffent l’atmosphère. Même si la recherche de la lumière naturelle peut être en contradiction avec la limitation des apports solaires pour le confort thermique, les protections solaires mis en place de cette façade épaisse ont permis à la fois de gérer les surchauffes et les problèmes d’éblouissement. Et c’est dans cette perspective que les architectes de la reconstruction ont mis en place le complexe loggia et brises soleils pour contrôler les apports solaires. Ainsi, les résultats de la simulation d’éclairement ainsi que la parole de l’habitant confirment que les pièces orientées sud-est et jouxtant la façade épaisse baignent dans la lumière en hiver tandis qu’en été, elles sont protégées.

« Il est bien orienté, d’ailleurs, les chambres de mes filles sont orientées sud-est, il y a toujours du soleil qui y pénètre ; et tu te sens bien en hiver car il fait « chaud » (defyin دافيين) et en été, il fait frais. » Insaf

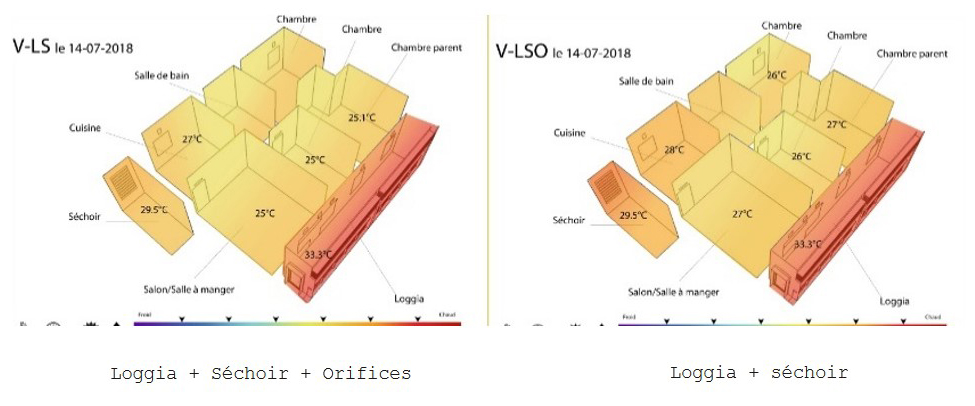

Au niveau du confort thermique, la combinaison loggia et orifices va avoir un impact sur l’ambiance thermique intérieure. Par exemple, pour la journée la plus chaude de l’année 2018, c’est-à-dire le 14 juillet à 15h, l’ouverture des orifices (dans le V-LSO) ne va engendrer une hausse de température de 2°C que si on garde les orifices fermés (V-LS). Dans le cas où les orifices sont ouverts, l’air chaud du vent du sud-est (Ch’hili) va entrer dans les pièces pour augmenter davantage la température. Toutefois, la température opérative reste dans la limite supérieure de la norme à savoir entre 25 et 27°C pendant la saison estivale35.

Source : G. Jallali 2022